Photography by David Vernon

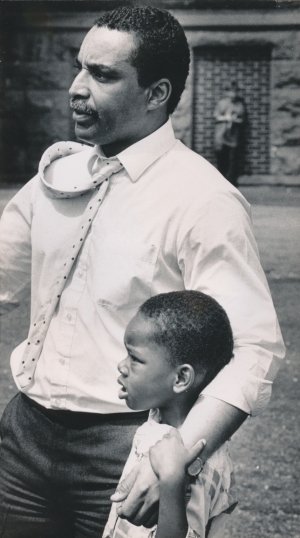

His mother taught that service to others was one of the greatest gifts we can give—a lesson Ken Hinton never forgot. He’s been called an “urban school pioneer” for a decades-long career in Peoria Public Schools District 150—but more importantly, he was known for his caring, commitment and compassion. For some of the kids he took under his wing, Mr. Hinton was the only father they ever had.

Born and raised in Peoria, Hinton graduated from Manual High School in 1964 and went on to Bradley University, where he attended classes while working multiple jobs around the clock and starting a family. Bypassing a career in law, he again took his mother’s advice and became an educator—one of the finest Peoria ever had. After teaching at Irving School for nearly 13 years, he became assistant principal, then principal at Harrison School, and served briefly at Trewyn before overseeing the 1993 launch of the Valeska Hinton Early Childhood Center—an internationally known model for early childhood education.

After several years as an assistant superintendent in Peoria Public Schools, he became a regional vice president of Edison Schools, Inc. in New York. But when his hometown district needed him, he returned to Peoria, serving as superintendent in a stint that stretched from 120 days to more than five years. After a brief period of retirement, he answered another call—taking the reins at Carver Community Center, which had closed suddenly amidst an uncertain fiscal future. A former “Carver kid” himself, Hinton knew well its importance to this community, and he’s still there today, serving as executive director.

He and his wife, Rita, have five children and 12 grandchildren—and despite being spread across the country, they are as close as his own family was as a child growing up in post-war Peoria.

Let’s start with your parents and their early influence on you…

My father’s family came to Peoria at the turn of the last century. My mother moved to Peoria after the Depression. Her father owned a large farm in southern Illinois, but with the collapse of the economy, they lost everything.

My dad worked all his life as a printer, but I think my mom had a bigger influence on me, in regards to thinking about others and realizing that you’re important, but others are more important. We were always taught to respect and appreciate education. Because it was denied to so many of us, education was always stressed in our household.

My mother graduated from high school, but my dad never did. She went to a two-year school and became a physical therapist. He and his older brother, Uncle John, dropped out and went to work. One story I never will forget was that they only had one pair of shoes—so one brother would wear the shoes to school one day; the next day, the other brother would.

Dad dropped out when he was 12, but you never would have known that. He was very well-read. In his early years, he worked in the printing shop, and the owners saw he had a talent. They eventually brought him in, and he ended up owning part of the shop before he retired.

What were your hobbies as a kid?

I loved to read. At Roosevelt, we could only check out one book a week—but the librarian broke the rules for me and would let me check out more than one… I read constantly. On Saturday mornings, rather than watching cartoons, I would go to the library to read and look at the different historical and travel magazines.

I also put models together—airplanes and ships—and I loved chess, mostly in my high school years. My mother rented rooms in our home to Bradley students, and there was a chemistry major who I became good friends with. We would start a game on Friday and play 24… 30 hours straight!

Tell me about the service club you and your friends started in high school.

We started our Illiopian Club in 1959 or 1960. We came together for camaraderie, but because of our background and parents… we did a lot of community service. All of the guys were involved in different churches. We did a lot of good things, and we had fun doing it.

We still meet every month, and we [also] have a breakfast club. On the third Wednesday of the month we have our regular meeting, where we determine who we’re going to help. For Thanksgiving, we worked with Kroger and were able to feed a number of families. We did the same thing at Christmas. And then people will come to us… [who] don’t have any clothes or furniture, and we help them out. We repair things. We have electricians, carpenters, plumbers… We do just about everything. We just finished donating to some young people to help build a house in Haiti.

It’s fascinating that this club you started as a teenager still exists, all these years later!

It’s fascinating that this club you started as a teenager still exists, all these years later!

People say that all the time. In fact, people have asked us to write a book because we’ve had so many unique experiences in our many years together. We’ve been together so long; we knew each other before we knew our wives! And when one of the guys has a difficult time, we try to help. From the very beginning, it’s always been that way. We love each other like brothers.

Let’s talk about Carver Center and its impact on you as a kid.

I took my first piano lessons at Carver Center; I must have been four or five. As a teenager, it was a positive place to go… a place to play basketball, ping-pong or pool. You didn’t have to worry about fighting or gangs, or anything like that. The adults were very focused on the kids being well-behaved and directed towards positive outcomes.

Carver had one of the most unique staffs at that time—a lot of people who became well-known in Peoria. Dr. Dorothy Cornish, who went on to ICC. Juliette Whittaker was the one who got Richard Pryor started. Miss Washington did the arts, my piano [lessons] and things like that. And Frank Campbell… just a number of really good people. I’m remiss for not naming everybody.

Did you know Richard [Pryor] when he was there?

I saw him. In fact, I used to go to his grandparents’ pool hall… I was there when I shouldn’t have been (laughs). But he ran with an older group.

So you went to Manual High School?

Yes, I did. At that time Manual only did 10th, 11th and 12th grades. I went to Roosevelt for seventh, eighth and ninth grades, and I went to Manual my sophomore year. Our class, the class of 1964, was the first graduating class from the “new” Manual (which is old now) that was there a full year.

1964 was a landmark year for the Civil Rights Movement. What do you remember about that time period?

It was an awakening time in regards to race. There weren’t issues at Manual. Our club was going on, and we were at some of those meetings… but it wasn’t until I got to Bradley that I really became more aware of it.

As a child here in Peoria, the first time I experienced [racial discrimination]… There was a store on the side of the Palace Theater on Main Street. A friend and I went in to buy a pack of Doublemint gum, and we were told we couldn’t. As a child, maybe we were too young [to understand]. We just went on our way. I found out later that’s what had taken place.

But in 1964 and ’65, it started to erupt here in Peoria: that people weren’t being hired for different jobs and professions. It was an awakening. When I got to Bradley, [with] some of the classes I took in sociology… I became much more aware of what was taking place.

There were also protests against the Vietnam War, the sexual revolution… all these things were happening at the same time. Was there a sense for that on campus?

There were also protests against the Vietnam War, the sexual revolution… all these things were happening at the same time. Was there a sense for that on campus?

There really was, but it hadn’t gotten to the point where it had become extremely intense. That started to happen towards the end of my [academic] career. I got married in 1966, and my life was really full. I was in class or on campus from 7:30am to 2:00 or 2:30pm, then I had to work at Caterpillar from 3:18 to 11:18pm, then I was up half the night studying. And I worked another job on Saturday. I was aware of the resistance to the Vietnam War, but I did not participate in the demonstrations. I was aware of the concerns as far as equality in regards to people of color, and women were also just starting to rise in terms of their unequal treatment. Me, I was trying to start a family and go to school. So it was a very busy and hectic time.

How did you meet your wife?

I was driving down the street and I saw this pretty girl standing in front of her house. So I put my foot on the brake and backed up (laughs). Two years later, I proposed. We got married very young, and we’ve been together ever since.

When you were in graduate school at Bradley, did you already know you wanted to be a teacher?

I was going to go into law, and I looked at going to school in Kansas or Washington, DC. Because I got married and I was a mid-year graduate, my mom suggested I try teaching out. I said, Mom, everyone in our family is a teacher, professor, principal or dean… I don’t want to go into teaching! She said, just try it! (laughs)

So I went out to the [District 150] administration building, and they needed a sub at Irving School. When I went to Irving, the principal took me into the room… The kids were running back and forth, and things were being thrown. And this girl said, we’re going to run you out of this building. The principal didn’t say anything! So I said, let’s see you do it.

The next day, I had my suit and tie on, and I walked into the classroom. You’re supposed to say, “Good morning, my name is Ken Hinton, and I’m here as a substitute.” I said, “Good…” and I never got “morning” out. Every kid in that room took their pencil, and the louder I spoke, the harder they hit their desks.

So I said, I want the biggest and the baddest—let me have them first. And [a young man] stood up. I said, give me your best shot… and WHAM! He hit me. He didn’t know that I wrestled. So I picked him up and threw him against the wall… Tie undone, suit torn, watch gone… I walked back in the classroom and said, who’s next? Another kid stood up. And then, over my right shoulder, [that young man’s] arm came down, and he said, sit down.

That’s how I started my career! When I left, you couldn’t tell them from any other classroom. The kids were well-behaved, and when the last kid walked out… a tear came to my eye. I knew at that time: this is what I want to do.

I never had any problems after that. I guess the reason I didn’t… These children were my kids. I’m not going to let my kids—my flesh and blood—act like they’re insane or disrespectful. That’s not going to happen. And many of these kids would come back and say, Mr. Hinton, you were the only father we ever had.

I was at Irving for almost 13 years, then I went to Harrison—a school that was in great need of structure and support.

Were you a principal now?

I was an assistant principal… then I became principal. We had a lot of students, and a lot of behaviors and attitudes that had to be changed.

What were some of your strategies to create this change in behavior?

When I first became principal at Harrison, school started at 9:00, I believe. The two secretaries would go to the counter with a pen and a pad, and they would write passes for kids coming in at 9:10, 9:15, 9:20, 9:30. So I sent a letter home to the parents. I said your child could be late three times; on the third time, I’m sending them home—and they cannot come back to school unless you bring them.

When the parents started having to come in, the secretaries weren’t at the counter any longer. The kids were there on time.

I would not allow fighting. I’ll never forget, one parent said, Mr. Hinton, you don’t understand, here you have to fight. I thought, when I go downtown, do I have to fight? When I go to the mall, do I have to fight? When I get on an airplane, do I have to fight? I don’t think so. That’s not going to work here either. And I am proud to say that after two or three years, I never had a suspension.

Sometimes kids wouldn’t get their physicals and dentals, and they would be kicked out of school. We stopped that, too. I told the parents, once they get here, they’re mine. And if I see that my kids are beaten or hungry, I’m calling DCFS. You don’t have to ask who did it, I did it.

I remember when my kids were coming to school, and some of them were not clean. And I know what it feels like when you don’t have things, because we were very poor [growing up]. I know you want to feel good about yourself… so I asked for a washer and dryer.

I wrote to every manufacturer in the United States… Whirlpool responded, and told me to go out to Klaus Radio and pick up a new washer and dryer. Once I got it to the school, they said we don’t do that in the District… But we [eventually] got it installed.

So when my kids were dirty, I saw to it they were clean. If they didn’t have a coat, I saw to it they had a coat. I tried to be as holistic as I could because I knew they had great potential.

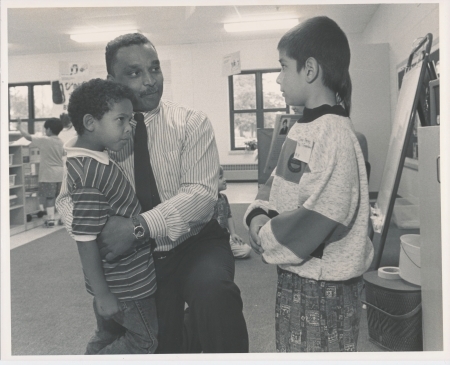

Tell me about your time at the Valeska Hinton Early Childhood Center. What was the impetus for starting this school?

Tell me about your time at the Valeska Hinton Early Childhood Center. What was the impetus for starting this school?

When I left Harrison, [then-Superintendent] John Strand asked me to be part of the group that helped put the school together. They had already developed the philosophy and structure. My [job] was to start hiring staff, work with the construction people… and I traveled around the country to bring best practices and ideas back to Peoria. The school opened in July of 1993.

The philosophy was that kids who were poor, or minority—if you give them a solid start from the very beginning—can do as well as any other kids. They did that by getting the best minds of early childhood education together, from the University of Michigan, University of Illinois, University of Wisconsin… The best thought and science at the time was put together at Valeska.

There was another major premise: that the teachers, the parents and the administration were equals… and you worked collectively, as a team, for the best outcome for the kids.

We had people coming from all over the world to visit this school. Wales, England, Australia… We couldn’t teach because we had so many visitors! So I said, if you want a tour, we’ll charge. $300 didn’t keep people away, what about $500? When I left, we had thousands of dollars in the bank, and the school was not in need of anything.

Was Valeska Hinton a relative of yours?

Yes, she was a relative of my father’s. We called her Aunt Terry. She was a very progressive woman who fought for civil rights and women’s rights.

How was the center different from Head Start or a similar program?

It’s changed from when I was there… but it was different in that it was year-round, and parent participation was required. The parents, teachers and I would meet once a month, and a discussion came up about the school being such a good experience, they wanted only the kids of parents who are going to support their kids in it.

If you wanted your kid at the school, you had a card. Each time you came to the school or participated in an event, you got a stamp or punch. When it came time to re-enroll your kid for the next year, you had to have at least 36 stamps or punches on your card. If you had less, you’ve already selected yourself out. That’s one of the ways it was different. But we had two Head Start classes [too], so there was a partnership between Head Start and Valeska.

If this model was successful, why did it change?

It required a lot of change in the system… [and] a lot of staff development for the teachers to stay in tune with the new information coming out, which requires a financial commitment. There’s travel involved, and then there’s understanding the philosophy and the science that goes into it.

The science is out there. If you put the money in when children are young, you’re miles ahead when they’re older. I’m sure it’s still applicable: for every dollar you spend now, you save $7 in the future. But our country doesn’t do it. Where does more money go: to high school, or to pre-K, kindergarten, first grade? It’s high school. It should go the other way, if we’re serious about making a difference.

We have kids [from Valeska] who are now doctors, lawyers, teachers and carpenters, and they’ll tell you it made a difference. So why doesn’t our country do it when we know the answer? That’s a good question for all of us.

Why did you leave Valeska?

The superintendent, John Garrett, asked me to be an assistant superintendent. That was 1998, and I was assistant superintendent until 2002. Then I retired from the District, and I was hired by Edison [Schools]. I was stationed out of New York and worked with them for two years; then the District asked me to come back for 120 days… which ended up being five-and-a-half years, as superintendent.

How did 120 days become five-and-a-half years?

The District was in great need—it was a very challenging and difficult time. But they asked me to stay, and I said I would. So I went back [to school] and took my tests, I got my superintendent’s endorsement and stayed three years. Then they asked me to do another three years, and I said I would. But I retired before I completed my last term… I found out my wife had MS, and my health was not the best either, so I told them I couldn’t stay. I wanted to spend as much time as I could with my wife, while we were both able to do so.

What were some of your proudest achievements during your career?

The thing I’m probably most proud of is breakfast. One morning when I was at Harrison, I looked across the field and saw somebody in the dumpster. This little girl was skinny as a rail; she and her brother were looking for food. So I started worrying the District about trying to get breakfast in school for the kids.

I got a call one morning… [that] they were going to use Harrison, Tyng and Irving as pilot schools for breakfast, and I really feel good about that. I’d read a study about how important breakfast was, and the percentages and numbers that were increased when kids eat breakfast. So that was another motivation, besides kids being hungry. And there were less discipline issues.

I also feel good about the health clinics in the schools. They had tried to do it at Manual, and it was fought hard and never happened. But after a year of working with people from the hospital, Peoria City/County Health Department and the [College] of Medicine, we came up with a health center that was able to happen. I have to give kudos to Methodist, because they were the ones who stepped forward and said they would try it.

The health centers started at Valeska and eventually went into schools throughout the city, so I’m very proud of that. I’m very pleased to have been part of the Early Childhood Center… to work with such fine people. Another thing I feel good about: when I left the District, it was in a financial position to carry on.

So tell us about those first few years of retirement.

So tell us about those first few years of retirement.

I was off for about two years, and I had no idea life could be as good as it is. My wife and I did a lot of traveling, spending time together, and just doing nothing. I had never had that in my entire life: to get up and not be obligated for hours and hours.

Then in 2011, I get a call that Carver Center has closed. And [Rita] says, you’re not doing anything, why don’t you help? So we started looking into Carver and found out that there were serious things that needed to be addressed. Their infrastructure had pretty much fallen apart, and there was no revenue or income stream to support it—that had all gone away. But it was so important to our community… There are those of us who feel we can’t let this institution go.

And now you’re the executive director. How did that happen?

I came on to help see to it that a business plan was put together, and it became apparent that much more needed to be done. Since then, we’ve redone the infrastructure, the financial infrastructure, the operational and maintenance plans… It’s all been redone to put the center into a position where it can once again support our community. Because it really does serve as an information point, a place for activities, a civic space… We provide lunch for children during the summer. We host basketball tournaments. Fraternities meet here… I could go on and on.

And there’s a big focus on the arts this year. Tell me more about that.

Let me just say this. Peoria was recently recognized as being one of the worst cities for African Americans. Why? A number of reasons. Our children leave. What do we have that keeps our kids engaged and involved? We, as a community, need to do that. Not only for children of color, but for all children.

If you go to a [large] metropolitan area, there are opportunities for people to become involved or get engaged. Our yearlong celebration of the arts is trying to bring back an aspect to Peoria that we had in the ‘50s, when well-known personalities would come through: The Jackson 5, James Brown, Joe Louis, Jesse Owens…

When [saxophonist] Gerald Albright was here in December, he sat right here in a room full of people, and the kids talked to him. The purpose was to provide an opportunity for people to be exposed to artists in a small setting. The artists have agreed to either work with or speak with kids, the day before or day after. The other huge thing is they will meet with “regular” people. When my wife and I go to St. Louis to see jazz, we don’t get a chance to talk to [the performers], but they will here. Do you think that could make a difference in someone’s life? It’s happening here at Carver.

We’re also going to be doing music and theater. We’re working with a gentleman from New York who’s doing an off-Broadway play—I asked him if he would bring it back to Peoria once he finishes. And then we’re going to do something that I need support from the community on. We’re going to be doing talent shows. There are people here in our community who have the ability, but no place to perform. We are going to provide those opportunities.

Carver is a great asset to our community—we have to do our best to see to it that it continues on. For that to be understood, you just need to spend a little time here and see who comes through and the people who need help, who need support, who need direction. That happens here. It’s a great facility.

Anything else you want to add?

I’ve been blessed to have worked with some magnificent people: teachers, administrators, parents… and business people, too. There are some who would call me when I was at Harrison and say, Ken, I’m going to give you $5,000—but I don’t want you to tell anyone where you got the money. We’ve got those kinds of people here in Peoria, who help others and don’t want to be recognized.

I believe we are here to serve and to help… that’s how I was raised. As I’ve had time to reflect on my past work years, what always comes to the top have been the blessings I’ve received from my students, their parents, and the wonderful educators and people I have been so privileged to meet and work with. iBi