A new book traces the aftermath of the Maytag factory closing in Galesburg.

Boom, Bust, Exodus started for me on October 11, 2002. On that morning, Maytag stunned Galesburg, Illinois, when it announced that it would close its enormous refrigerator factory there and move production to a maquiladora (export-oriented factory) in Reynosa, Mexico. There was profound sadness, fear and anger in Galesburg, and some said the city of 33,000 would die—that it would become a ghost town.

I had just moved to Galesburg in 2001 to join the faculty at Knox College. I grew up in a small town in Indiana, but not a factory town like Galesburg. I wanted to understand what was happening around me, and how Galesburg—its workers, its families, the community—would fare in the aftermath of the factory shuttering.

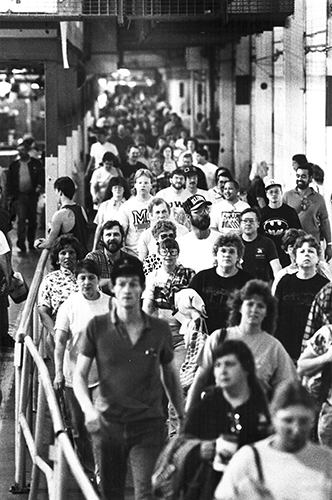

For a century, manufacturing on Galesburg’s southwestern edge had anchored the local economy. In 1905, men began to hammer out steel plowing discs in a two-story brick workshop. In the early 1970s, industrial Galesburg’s heyday, a sprawling patchwork of buildings on that same spot—called “Appliance City” by some—buzzed with nearly 5,000 workers, producing some half a million refrigerators and freezers a year. Dave Bevard, a longtime worker at the factory, remembers his first day in 1973 when he walked into a disorienting buzz of activity: speeding forklifts, the clanging of metal presses, and armies of women doing nimble-fingered piecework at the parts tables.

Today, over a decade after closing, the former Appliance City site—the size of more than 40 football fields packed together—is mostly rubble and weeds. Looking at it now, it’s hard to imagine this place once meant so much to so many for so long. Yet it’s important that we do not forget.

That closing—and so many others like it—helps to explain our economic predicament today. The manufacturing jobs lost when the Maytag factory shuttered in 2004 were a couple thousand of the 5.8 million jobs lost in the 2000s. Illinois lost 37 percent of its manufacturing jobs, most of them before the Great Recession, a devastating blow to the state’s middle-class families.

A Tale of Two Cities

To understand Galesburg in the NAFTA era, I realized I needed to follow the jobs south to Mexico. The city’s story was a transnational one now, and that was the only way it made sense to tell it. So my project expanded. From 2003 to 2013, I traveled to Reynosa, Mexico five times, and Boom, Bust, Exodus became a tale of two cities.

Reynosa is a city of about a million at the southern tip of Texas, just across the Rio Grande. There, I spoke to Mexican Maytag workers, economic developers, grassroots organizers, border economists, government officials and union leaders.

In Galesburg, that big Maytag refrigerator factory was an economic anchor. In Reynosa, Planta Maytag III, as it was called, was but one of more than 150 factories. This is a city where workers in the export factories put in an extraordinary 20 million hours each month. In the maquilas, nearly 100,000 workers make flat-screen televisions, women’s intimate apparel, stainless steel sinks, seat belts, windshield wiper assemblies and much more for U.S. consumers.

In the book, I detail the creation of modern-day Reynosa—the good, the bad, the ugly—and tell stories of ordinary people working the jobs that men and women in Galesburg once worked, at a fraction of the wages—typically between $1.10 and $1.50 an hour in take-home pay. Maquila workers are almost entirely migrants from Mexico’s south, seeking a better life for their children, but frustrated by their inability to provide for their families on paltry wages at the surprisingly expensive border.

These are not the middle-class jobs that President Bill Clinton and Mexican President Carlos Salinas promised when they promoted NAFTA as a solution to Mexican immigration to the U.S. They said Mexico would export goods, not people, once free trade came to Mexico, but they were wrong.

Getting By on Less

News accounts of factory closings and layoffs have been all too familiar in western Illinois. In Boom, Bust, Exodus, I follow the lives of workers for a full decade after the Maytag closing to understand not just the devastation of a layoff, but also the long, rocky path to a new life. A decade after the shuttering, the relative equality of factory life—where everyone earned about the same wage and had the same benefits—has given way to unequal outcomes. Some earn more today than they did a decade earlier, especially those who work at Galesburg’s booming BNSF Railway hub, which has benefited from growing international trade.

In general, however, people are getting by on less. The Maytag jobs paid about $15 an hour, more than twice the minimum wage at the time. One couple, Jackie and Shannon Cummins—who have two adopted children—went from earning a combined $76,000 in today’s dollars, to about half of that today, $37,000. For the Cummins family, this meant lowering the thermostat in winter, foregoing the trip to Disney and buying cheap food in bulk at Aldi. This is the new “normal” across western Illinois.

We hear a lot these days about inequality, and about the top one percent—really, the top 0.1 percent—getting nearly all the gains of growth. But there’s also what’s happened in Galesburg: downward mobility. The economic decline of the Cummins family also contributes to growing inequality in the United States. In fact, the Maytag case study is a good one for seeing how the gains at the top—for executives and big investors—come at the direct expense of workers at the bottom—and their communities. Maytag’s local payroll exceeded $60 million.

After Maytag

In Galesburg, people told me that Maytag had lost its moral compass. The company began to bring outsiders into management, and the focus shifted from quality products to cost-cutting, offshoring and shareholder value maximization. “How people in his position can sleep at night is beyond me,” Tony Swanson told The Register-Mail after the closing announcement in 2002, referring to then-Maytag CEO Ralph Hake. “I mean, how can they knowingly destroy thousands of American citizens’ lives and the communities they live in and still look at themselves in the mirror? If that is what wealth does to you, I don’t want any part of it.”

For decades, Maytag had been a quintessentially Midwestern company. Legendary CEO Fred Maytag had his company’s creed inscribed on the wall in its Newton, Iowa, headquarters. In that creed, “Mr. Maytag,” as Life magazine called him, preached “a just balance among the interests of customers, employees, shareowners and the public.”

I interviewed former CEO Len Hadley, who had steered Maytag successfully through rough patches in the 1990s. Hadley, a traditionalist and Maytag lifer, liked to say, “Our future lies with the past.” He was saddened by the company’s fall. “I thought I left them hardwired for success,” he told me in 2012. “I was astounded at how quickly the wheels came off.”

Maytag failed, yet Hake made off with a $10- to $20-million golden parachute, while communities like Galesburg suffered the consequences. In Galesburg, Medicaid enrollments doubled in the 2000s, and the percentage of low-income children in its schools shot up. I quickly understood, though, that former Maytag workers did not want to be viewed as victims. Jackie and Shannon went back to school; they scrimped and saved; they went to yard sales. They scrambled from job to job across the region and eventually settled near home with jobs they found more meaningful than factory work, even with their incomes halved.

The Maytag casualties—nearly half of them women—were mostly mid-life with families or nearing retirement, with little desire to start over or deal with the bustle of the big city, where wage prospects weren’t much rosier. Boom, Bust, Exodus looks at how many have found their niche tending patients at the hospital, working with kids in an elementary school, or coaching a junior-high basketball team. As Jackie Cummins says, “I think we’re just little old farm girls at heart. We love apple pie, baseball games. We’re just kinda cheesy Midwesterners.”

Galesburg endures because its residents have stuck it out to be close to friends, family and the way of life they know. This is what I wanted the book to capture: that gutsy Midwestern stubbornness to forge ahead in spite of what many saw as unfair and unpatriotic changes.

Moving Ahead

The good news is that we still have over 12 million manufacturing jobs in the United States, and some stalwarts of Midwestern manufacturing, such as John Deere, Harley-Davidson and Caterpillar, have survived, even if some have outsourced and downsized to do so. All the major appliance manufacturers have stateside factories. There is even talk of American corporations “reshoring” jobs back to the United States—including Peoria’s Caterpillar. As General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt argued in 2012, “Outsourcing that is based only on labor costs is yesterday’s model.” While reshoring is only a trickle, the trend is in the right direction.

America needs manufacturing to thrive, and there’s hope if we work together. In Newton, Iowa, the building that used to be known as Maytag Newton Laundry Products Plant #2 has been transformed. Today, workers there—many of them former Maytag workers—make wind towers. In a combined local, state and federal effort, Iowa is becoming a leader in green energy production, and that old washer and dryer factory is back in operation.

If western Illinois rolls up its collective sleeve, it can breathe new life into that spot on Galesburg’s southwestern edge—and others like it—as well. iBi

Chad Broughton is a senior lecturer in public policy studies at the University of Chicago. Boom, Bust, Exodus: The Rust Belt, the Maquilas and a Tale of Two Cities is available on amazon.com and at booksellers across the nation.