For Native Americans, the 18th century was a time of profound hardship.

Lake Peoria drew Native Americans to its shore for millennia—an oasis amidst a vast prairie and an abundant fishery surrounded by a food-rich landscape—and came to be known by the Illinois as Pimiteoui, or “fat lake.” Although the Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Ottawa and other communities fought to remain in the bountiful region, the settler population expanded in the first decade of the 19th century, and by the end of the conflict surrounding the War of 1812, few tribes would call Pimiteoui home.

European settlements had taken root on the continent’s eastern seaboard, and explorers probed ever deeper into the midcontinent. At first, trade spurred the mutually beneficial interactions between Europeans and Native Americans, but the European and then American thirst for land would eventually dominate life.

Striving to Retain Place

Many, and then most, Native American communities in the East were abandoned in the face of the swelling population of Europeans. Some tribes resisted and were defeated, some were consumed by disease, and some chose to retreat inland. As France, Great Britain, and eventually the United States competed for North America, Native American tribes juggled their allegiances with the deep-seated hope of retaining their place.

By the close of the American Revolution, settlers pressed deeper inland, especially along the Ohio River Valley, contesting and sometimes displacing tribes. In the process, the United States government sought to negotiate land cessions. The Treaty of Greenville of August 3, 1795, was the first in which the U.S. government staked a claim in Illinois, including “six miles square at the old Piorias fort and village, near the south end of the Illinois [Peoria] lake on said Illinois River.”

Questionable Treaties Cede Land

Questionable Treaties Cede Land

At the dawn of the 19th century, President Thomas Jefferson’s vision of an expansive United States was articulated to William Henry Harrison, governor of the Northwest Territories, who was headquartered in Vincennes on the Wabash River. Harrison set about to secure all of the land in the Illinois country. Treaties negotiated, sometimes under questionable circumstances, with the Kaskaskia, Piankashaw, and Sauk and Fox tribes transferred much of the Illinois country to the United States in three immense land parcels.

The idea that Native Americans “owned” the land was controversial among the tribes, to say the least, and the authority of any individual to sign a treaty ceding the land to the American government was also problematic.

In time, eastern tribes abandoned their native homelands and took up residence farther west. The Potawatomi, for example, moved from the upper reaches of the Great Lakes into northeastern Illinois in the late 18th century. By the first decade of the 19th century, they had established villages along the upper Illinois River and on Lake Peoria.

The Prophet and the Battle of Tippecanoe

Meanwhile, two Shawnee brothers, Tecumseh and Tenskatawa, would alter the course of relations between native people and the United States. Following a brief episode of unconsciousness, Tenskatawa awoke with the belief that he had been visited by the Creator. Soon thereafter, he became known as the Prophet, and people from many tribes traveled to his village to learn from his respected wisdom. At the same time, his brother, Tecumseh, challenged William Henry Harrison to stop the process of land cessions, appealing to tribes throughout the midcontinent to join a confederacy and oppose U.S. expansion.

In the fall of 1811, the real or imagined threat of Indian unrest encouraged Harrison to raise an army and march to the area of Prophetstown, located near the confluence of the Tippecanoe and Wabash rivers. There, the Prophet’s warriors attacked Harrison’s encampment, where, by many accounts, they fought to a draw. However, the Battle of Tippecanoe destroyed the influence of the Prophet, and provided Harrison a “war hero” reputation among settlers that he would later use to his political advantage in becoming our nation’s ninth president.

Growing Population, Escalating Tension

At the same time, the number and size of Native American villages on Lake Peoria increased with the addition of the Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Ottawa and other communities concerned with the continued expansion of American settlements. Distressed, in part by the losses at Tippecanoe, warriors from some of these villages attacked settlers on the southern Illinois frontier in retaliation. The territorial governor, Ninian Edwards, was increasingly beseeched to address the problem. In June 1812, Great Britain and America went to war, and in August, Native Americans massacred a military column retreating from Fort Dearborn at Chicago.

Despite numerous conferences among tribal leaders from the Lake Peoria villages, including Gomo, Little Deer and others, and between Edwards and William Clark, the Indian agent at St. Louis, suspicions grew that the villages harbored murderers and that the small French community of Peoria encouraged their depredations.

At War

In October 1812, Edwards launched a three-pronged attack on the villages at Lake Peoria. A cadre of 2,000 mounted Kentucky volunteers were to move up the Wabash River and cross the Illinois prairie to Lake Peoria, but they abandoned their efforts before they had travelled far. Meanwhile, Edwards led a horse-mounted force across country north from Fort Russell at present-day Edwardsville to Lake Peoria. His force destroyed two villages on the east side of the lake across from present-day Chillicothe before retreating.

On November 5, 1812, Captain Thomas Craig, in charge of two boats ascending the Illinois River, arrived in the French enclave of Peoria. Unknown to Craig, Clark and Edwards had retained the services of Thomas Forsyth to monitor tribal movements at Lake Peoria. Unconvinced by Forsyth’s appeals, Craig arrested a few dozen of the village’s inhabitants, burned part of the community and transported those he detained downriver to Alton. According to some accounts, Gomo witnessed these events and provided assistance to those left behind in Peoria.

A force under the command of General Howard returned in 1813 to establish Fort Clark. In the process of doing so, they destroyed other villages on Lake Peoria, including that of Gomo. Within two years, many of the tribes on Lake Peoria had been forced from their land, some crossing the Mississippi River.

Some of the Potawatomi and Kickapoo, in particular, tenaciously held their ground in the Illinois River Valley. They endured an ever-expanding frontier of American settlement, periodic raids that resulted in the destruction of their villages, and starvation brought about by their inability to range into their traditional winter hunting grounds. As the third decade of the 19th century approached, tribal numbers had thinned, and appeals to the U. S. government to secure territory were unsuccessful.

Last Stand

In the spring of 1832, Black Hawk and a group of some 1,500 followers would return from the Iowa territory with the hope of planting corn at Saukenuk—once the Sauk home village and now Rock Island—and perhaps challenging American settlement in the region. His return unleashed a substantial array of federal troops and Illinois militia determined to rebuff him. They succeeded, and at the conclusion of the strife, most of the tribes would leave Illinois, a place Native Americans called home for more than ten millennia. iBi

Michael Wiant is the director of Dickson Mounds Museum, a branch of the

Illinois State Museum and a National Historic Site in Lewistown, Illinois.

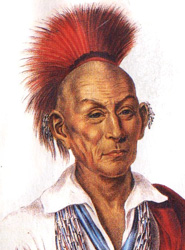

Black Partridge

Black Partridge

The life of Black Partridge (“Mucketypoke,” Muck-a-da-puck-ee), a Potawatomi warrior and chief, personifies the chaos of Native American life in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Illinois.

At the close of the Revolutionary War, the United States demanded that the British cede land they controlled which was occupied by Native Americans. Naturally, Native Americans challenged the right of the U.S. to take land without their consent, leading to the Battle of Fallen Timbers of 1794, in which Black Partridge fought. American forces prevailed, leading to the Treaty of Greenville of 1795, which ceded much of present-day Ohio to the U.S.

June 1812 found Great Britain and the United States at war again. Many tribes aligned with the British, and in doing so, created a powerful threat to the United States. That August, Black Partridge was among hundreds of warriors gathered at Fort Dearborn. Unable to convince the young braves to remain at peace, Black Partridge warned the fort’s commander, Capt. Heald, that there might be trouble. Soon after Heald’s column left Fort Dearborn, it was attacked. During the battle, Black Partridge rescued the wife of Lt. Helm, and his heroic effort was celebrated by a statue that stood in Chicago for many years.

According to some accounts, Ninian Edwards’ militia destroyed Black Partridge’s village on Lake Peoria in October 1812. A monument at the intersection of Bricktown Road and Illinois Highway 26 designates the location. However, additional research has brought this conclusion into question. Edwards’ own account indicates the village was occupied by Kickapoo, and other sources indicate that Black Partridge’s village was on Sand Creek (today Aux Sable Creek), near the confluence of the Kankakee and Des Plaines rivers.

Although an advocate for peace at Fort Dearborn, Black Partridge later reversed his position. In 1874, Nehemiah Matson speculated that the brutality of Edwards’ attack alienated Black Partridge. Thereafter, Black Partridge took part in battles at the River Raisin in January 1813 and was involved in an unsuccessful attack on Fort Clark at Peoria later that year.

The Native American villages on Lake Peoria continued to draw the ire of American forces. Gen. Howard’s expedition in 1813 destroyed two villages, including Gomo’s village near present-day Chillicothe, which had been abandoned during the winter hunt.

In May 1814, Robert Forsyth, the Indian agent in Peoria, indicated that “all of the Potawatomies of the Illinois River will plant the corn at Gomo’s village,” but it is not clear if Black Partridge relocated his Sand Creek village to the region at that time.

Gomo died in 1815, and Black Partridge assumed more responsibility among the Potawatomi on the Illinois River. He signed a treaty of peace and friendship with William Clark and Ninian Edwards, among others, at Portage Des Sioux in 1815. But by this time, it was clear that the expansion of American settlement was inexorable.

The Potawatomi continued to occupy summer villages on Lake Peoria and travel downstream to their winter hunting grounds along the lower reach of the Illinois River, but this way of life became increasingly difficult. Black Partridge would not live to see the eventual transformation of Potawatomi life; he died in or near Gomo’s former village in 1820.