As Director of Public Affairs for Caterpillar Inc., Byron DeHaan established and led a diverse range of communications initiatives throughout his 42-year career with the company. A Navy veteran and lifelong student of culture and religion, he traveled to nearly 30 countries on five continents—ever curious about the world around him, and always ready to help where he thought he could make a difference.

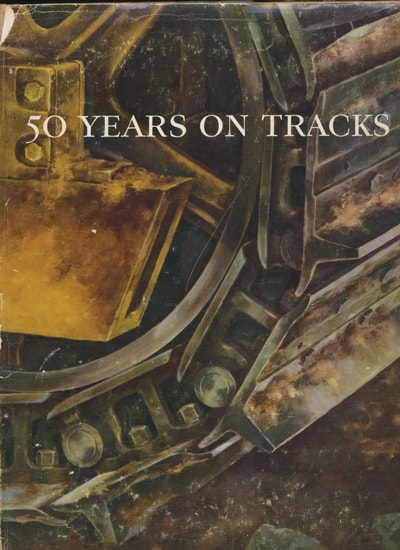

Born the son of two Dutch immigrants on July 18, 1926, DeHaan joined the Navy at age 17, graduated from the University of Kansas with a degree in the emerging field of industrial management, and landed a job at Caterpillar, working in various capacities before settling into a communications role. He was the primary author of 50 Years on Tracks—the first book on the history of Caterpillar—and helped develop the Public Affairs department, which evolved to include five functions—Governmental Affairs, Community Relations, Caterpillar Foundation, Employee Information and Public Information—and became a model for companies worldwide.

Always community-minded, DeHaan was involved in Peoria’s post-war transition to a council-manager form of government and helped promote the initiative to establish Illinois Central College. In the mid-1960s, he became active on the local civil rights scene, serving as Caterpillar’s point person for equal opportunity and co-developing a bus tour that helped awaken the community to the need for change—and led to the first fair housing law in the state. He subsequently became involved in civil rights statewide, chairing the Illinois Commission on Human Relations under two governors.

Upon retiring from Caterpillar in 1991, DeHaan went back to school, taking “a few college courses” that earned him more than 200 credit-hours at Bradley and ICC. He also deepened and intensified his love for the arts: singing, playing the guitar, painting, throwing pottery and writing poetry—and garnering numerous awards for his way with words. Breviary, a collection of 32 of his poems, was published by Converse Marketing in 2004.

In 2000, DeHaan became co-chair of the Museum Collaboration Group, where he played a leading role in the development of the Peoria Riverfront Museum. He was married to Sylvia DeHaan—the love of his life—for 45 years, and has four children, six grandchildren and one great-granddaughter.

Let’s start with your family history… Tell me about your grandfather who came over from the Netherlands.

His name was Albert Blocker, a prosperous bulb grower and flower merchant. During World War I, that business declined rapidly… so he decided to immigrate to the United States. He came over with his oldest son and settled in Western Springs, near Chicago.

So he prepared the way, and my grandmother and the other four kids, including my mother, came over comfortably—they didn’t have to go in storage. But, they shipped their worldly goods on another ship, which was sunk by a submarine. Then they landed in New York and took rail transportation to Western Springs.

That was 1916. My grandfather worked in greenhouses… and eventually started his own business. He bought a farm in southern Michigan to raise bulbs and grow flowers—I used to go there when I was a kid. My mother went to nurses’ training in Benton Harbor, Michigan and became a nurse. Then she met a man named Conrad DeHaan.

My father’s family came from the Amsterdam area. He was first-generation—he went to Dutch schools and churches and so forth—[and] lived on the far south end of Chicago. So my mother, a Dutch immigrant, met a young man, who was the son of Dutch immigrants. These things often happen.

My father only had an eighth-grade education; he was a farm boy. He was drafted and [served] in World War I in France. They were married in 1924. I was born in 1926 in La Grange.

What were some of your earliest memories?

There were a lot of open areas in Western Springs—a lot of room to play ball and a good community atmosphere. My parents wanted good schools for my sister and me—that’s why we moved there. So I went to [grade] school in Western Springs and high school in La Grange.

In the 1930s, everybody was broke. I wanted to get into Scouting, but my father said we couldn’t afford it. My mother knew that in the neighboring town, there was an Episcopal choir that ran on the English model—all male—and really good. Since I was not going to be a Boy Scout, my mother signed me up… as a boy soprano. So I was in the apprentice choir for a year, then I became a soloist for the senior choir when I was 12. This was my substitute for Scouting: singing three times a week.

I was also active in sports… but I was a late grower. [La Grange] had a lightweight basketball team, so I played on that, not a star or anything. I did play on the golf team and got to be pretty good at it. I was the number-three man, and we came downstate to a city I had never visited before: Peoria, Illinois. The state finals in 1943 were at Mt. Hawley Golf Course.

Through most of [World War II], the draft age was 21, but they needed more people, so they dropped it to 18. So here I am coming up on 18, knowing that by the time of my birthday in July of ‘44, I would be drafted. I did not want to be drafted, so I joined the Navy.

Why the Navy?

I wanted to fly the Navy Air Corps—the V5 program. In Christmas of ‘43, a dear friend and I took the train to the Loop, where they were considering recruits. This took several hours, and they had one of those books with all the little dots to determine if you’re color-blind. Going back, we had a big laugh over the fact that he couldn’t see any of the numbers—he was color-blind and didn’t know it. Because of that, he flunked. I was accepted, and they said you can finish high school, but July 1st you have to report to… a college campus in Northwest Missouri. [I took] a combination of naval science and some college courses… then boot camp.

The program was supposed to last eight months, then pre-flight in Olathe, Kansas and flight training at Pensacola. Well, none of those things happened; the Navy had plenty of pilots. This was late ’44; things were winding down. I went through a variety of training programs and had a little sea duty on a battle ship, but that was after the war was over.

Where did you go?

Where did you go?

I was in the Pacific on the USS Iowa for five or six weeks. Then I was mustered out, but continued my Navy connection. So when I graduated from the University of Kansas in ‘48, I also received a Navy commission. Then in 1950, during the Korean War, I got a letter saying report to Little Creek, Virginia for PCEC-873 in the Atlantic fleet. They gave me about 10 days! (chuckles) This was while I was at Cat.

How did you decide on industrial management as your college major?

I was in mechanical engineering through three years at Kansas U… I did well because I could handle the math, but it was very abstract. Then they announced a program called industrial management, which was basically three years of mechanical engineering and 50 hours in the business school—accounting, marketing and statistics, things like that. So I got a BS in what was called industrial management.

I graduated at a very happy time—anybody with a warm pulse could get a job. I interviewed at a dozen companies… and got several offers. As it happened, my father became a salesman with a used equipment company. He knew a dealer in the Chicago area; he and my father had been mechanics together for many years. He said Caterpillar had this terrific college graduate training program—he said he’d call down there and arrange an interview.

So I came to Peoria for the second time ever and interviewed, and they offered me a job. My first day on the job, the supervisor took me to the beginning of the engine line and said, “Byron, I want you to do three things: watch this first guy, help him, [then] gently push him aside and try to do his whole job in one day.” This guy was assembling rings on pistons, and the next guy was doing something more with pistons, then the next guy is putting them into an engine casting and the next guy is putting the crankshaft in, and so forth.

I did this on the engine line, the tractor line, the motor grader line, the cable control line… I became a foundry apprentice for a month, working with my hands, making castings and things like that. I was in the research department for a month; I was in the engineering area on a draft board. That was the most educational year of my life—and a full year on the hourly payroll.

Then I came into the sales department, and somebody picked up on the fact that I liked to write. The manager came to me and said, “I’d like you to come up to advertising and be a copywriter.” So I did that, and did quite a bit of traveling. I’d go with a photographer to a pipeline job in Tennessee… We’d be out for a week taking pictures, and I’d be writing stories. Then suddenly, I got the Navy recall and I was gone. But the folks at Caterpillar liked me and kept close track of me.

How long were you gone?

About a year, to a year and a half. This was a small ship… 90 people, 900 tons. Patrol Craft Escort—we were basically part of the Atlantic Amphibs. I was operations officer, like a Lieutenant JG… then I was asked to be temporary exec, at age 25. I was running the ship and really liked it, so I said to the captain, “I think I’ll just stay in the Navy.” And he said, “You’d be making a dumb mistake, because you’ll be running up against these guys from Annapolis. You’d probably get up to four stripes… but you’ll never be an admiral.”

So I wrote my boss at Caterpillar and said they’re going to let me go pretty soon because I was on an “in-early, out-early” program. I’ve got some additional GI Bill entitlement, so I’m going to law school. He wrote back and said to meet him at the Drake Hotel in Chicago… He wanted me to come back and take charge of what he called a history program. At the time, Caterpillar had no archives, and they were talking about doing something on the history of the company.

That was 50 Years on Tracks, the first book on the history of Caterpillar. I didn’t know what I was doing—and no one else did either—so I visited a lot of companies. Ford had a program, Ford at 50, in 1953, and I had books from IBM and DuPont. I probably visited 10 companies, just picking their brains… We had a very successful promotional program… Then they asked me to run Caterpillar’s first worldwide dealer meeting in 1955.

The dealers at the time had struggled through World War II. They weren’t getting product, so they had to make do—a lot of servicing, rebuilding old machines and so forth. Many were first-generation dealers who weren’t entirely sure they wanted to keep their money in the business.

They weren’t getting product because Cat was supplying for the war?

Yes. So we took dealers to the new engine factory, Building KK, and Building LL; then we took them on a Rock Island train to Joliet and Aurora; then to Decatur on buses—these were all-new factories at the time. I remember when we set up the tour at Building KK, there was a dynamic, young factory manager named Bob Gilmore [future CEO]. That was the first time I met him. He had 2,000 people working for him, and he just did a terrific job.

Harmon Eberhard was then president; I count him as one of the finest men I ever knew. He asked me to be an assistant—this was ’56 or so. I worked right outside his door… One assignment was to consider how Caterpillar could play a larger role in governmental/legislative affairs. So I went around to a number of companies and developed what I thought would be the ideal organization, and presented my findings to Eberhard, Bill Blackie and some others… We developed this Public Affairs concept, and they asked me to head [it] up. It ultimately included five functions: Governmental Affairs, Community Relations, Caterpillar Foundation, Employee Information and Public Information.

At first, it was just the legislative function. Public and Employee Information, then Community Relations came later, and the Foundation was the last piece. It was evolution, rather than revolution. We built a concept that became a model for other companies. I spent the rest of my career there, which I loved, and traveled the world.

This was also a good fit for Caterpillar. I remember one case: we were looking for an x-ray stress analyst, which requires a multiplicity of degrees… The company found an ideal fit. He had all the tools, he liked Peoria and he liked Caterpillar, but he couldn’t get a house because he was black. Peoria was very segregated, and we lost him because of this. About that time, Caterpillar became a civil rights leader on the leading edge of equal opportunity.

How did you get involved in the civil rights movement in Peoria?

In the early 1960s, my pastor at Westminster Church, Bill O’Neill, was on Peoria’s Commission on Human Relations. One day, he said to me that there was no one from the business community on this commission, so I [joined]… then I got Dewey Wilkins, president of Traders [Realty], and some [other] business people to come on. I eventually became vice chair, and spent a lot of time on it. I was very devoted to developing better race relations.

Peoria had a lot of problems… in areas like education, housing, employment, access to voting and things like that—no different than other communities, but we had good leadership that many other communities didn’t have. Most communities did not have the quality of leadership that I saw in John Gwynn [NAACP]; Frank Campbell, head of the Urban League; and Valeska Hinton, our executive director on the commission. I counted them as good friends.

When John Gwynn came up and led the demonstrations in the ‘60s, what was the reaction in the community?

The reaction was that this guy was a bomb thrower, a disrupter, and you had all the clichés about progress being one step at a time… They didn’t like all this protesting. But I got to know John. I didn’t agree with everything he did, but I thought he was a highly moral guy. So behind the scenes, several of us raised money to support him. We, in the business community, said this needs to change.

Can you describe the bus tour you created?

A black physical therapist and I developed the bus tours. We did this many times, with many community groups. We started with the city elders—we said we aren’t going to do any preaching; we are just going to show them… Here’s a nice, new house, and it’s in a slum. It was [owned by] a dentist who had plenty of money, but couldn’t build on the north end of town. Peoria was very segregated—no blacks living outside of the south side. When Frank Campbell came to town, he had to go into the ghetto—a guy with a master’s degree and so forth, running the Urban League! So we just went up one street and down the other, and talked about slum housing and slum lords—but there was no preaching. We took them through the red light district, and when they got off the bus, [everyone] was quiet.

Eye-opening?

Eye-opening. And the phone rang one day—it was Bill Blackie, president of the company. He said, “I want all our officers to take this tour, because I don’t think they understand the problem.” Then we had the Chamber of Commerce, church groups, professional groups… It made it possible for Peoria to be the first city in the state to pass the fair housing law. I’m very proud of that.

Then I became chair of the Illinois Commission on Human Relations, the statewide civil rights agency. [Governor Otto] Kerner called our CEO, Bill Franklin, who followed Blackie in the job, and said, “This commission is moribund… I want somebody to shake it up, and I need a Caterpillar guy.”

So I became chairman of this commission, and I shook it up and got some business people on it… We developed service training for teachers, so teachers could be more racially conscious. We developed a very innovative program for police—sensitivity training—and hired a black policeman from Chicago to run the program. We had a Catholic nun running our education program. We had a fair housing program and we used the Peoria law, which I helped write, as a template.

After retiring in 1991, you took classes and became very active in the arts. Tell us about that.

I started out with four very different courses: Shakespeare, historical geology, art history and music appreciation. I was on the Bradley campus three times a week… and one thing led to another.

I signed up for a sketching class with Ken Hoffman. We sketched Westlake Hall, the tower… and he said, “You seem to have a bit of an affinity for this—have you thought about oil painting?” I thought I’d give it a try. I did not have a great talent… but I did that for six semesters, and Ken encouraged me. The same was true for ceramics under Randy Carlson. I was throwing clay all over the room [but] I kept at it… and got to be fairly good, and I loved it.

I started singing with the [Bradley] Community Chorus before I retired, so I just continued that. I did that for 18 years. I played some guitar… and I took some classical guitar lessons. I developed a program—a travelogue that ran about 40 minutes—and visited a lot of nursing homes, playing a guitar and singing.

What led you to start writing poetry?

What led you to start writing poetry?

One of my classes at Bradley was “Introduction to Poetry” with Kevin Stein. Then he got me into his poetry workshop, and each week, you have to develop a poem. You stand up and read your poem, and people throw rocks at you. He said, “Why don’t you enter the annual competition?” So I developed the lead poem in my book, “Requiem for Mozart and Us,” and that won the prize.

Then I took a workshop with Jim Sullivan at ICC… I was doing all these workshops and poems, and one or two were published. Jane Converse saw something in one of my poems and asked if I had more… Breviary was her idea. I said, “I’ll put these poems in a three-ring binder and show it to Kevin and Jim. If they agree to do a blurb on the back, fine.” They agreed, and we were off and running.

[Converse Marketing] paid for the development, the typography, everything. The only thing I paid was the printing bill. I have since gathered subsequent poems into a three-ring binder with a different title: Vade Micum. It’s Latin; it means “go with me.” It’s a little reference book that goes with you—you put it in your pocket.

What inspired the poem you wrote for the dedication of Preston Jackson’s Underground Railroad sculpture?

Rebecca Bourland called me and said Preston has this sculpture he’s been commissioned to do, honoring the Underground Railroad and the exact location where the Moses Pettengill house [a stop on the URR] was. The dedication was set for October 2008, and she wanted me to write a poem to read at the dedication. I was very flattered.

The first thing I did was call up Preston and said, “I want to spend an afternoon with you; I want to understand what you’re trying to do with this.” He was very enthusiastic. The second thing I did was bore into the history of the Underground Railroad in Illinois. The third thing I did was read a book on Abraham Lincoln in Peoria, which had to do with this great [anti-slavery] speech he made in 1854.

Unfortunately, the reading came about 10 days after my wife died of pancreatic cancer. But I read the poem, and Mark Spenny [of CEFCU]… came up afterwards and said we’re going to frame this. He framed about 10 copies, gave one to the mayor and so forth. The poem is on the wall as you walk into the Civic Center.

I wanted to ask about your wife. How did you meet?

A friend of mine, in 1962, said there’s this teacher at Manual… She was renting a little slab house in Mission Hills. She had this beautiful five-year-old boy and a thoroughbred collie dog, Mike. I went over there and it was just like finding home.

Sylvia was a wonderful person—the greatest thing that ever happened to me. The oldest boy, I immediately adopted… then we had three more kids. We found this house on Sleepy Hollow Road that was owned by Caterpillar at the time. We just loved it. We were married for 45 years—it was a long run.

Tell us about your work with the Museum Collaboration Group.

I was on the board of the [Peoria] Historical Society, and we decided to build a history museum—which, as it turns out, would have been a terrible mistake… So we went to [then-Congressman] Ray LaHood. It turned out he had been approached by Lakeview [Museum], which was talking about expanding…

There were about 10 groups involved, and we all convened in Ray’s office on August 30, 2000. Ray was very good at getting people together. He went around the room and said the Historical Society has approached me, the African American Hall of Fame approached me, Lakeview approached me and the [IHSA] approached me. He said the federal government hasn’t got the money to support all these things… so we agreed to work together.

We weren’t sure what the outcome would be. We talked about options… Then Brad [McMillan] and I hit on this idea of bus trips. We would load a bus up—and Caterpillar paid for these buses; they never got credit for that. We took a bus to Kalamazoo… We stayed overnight in Grand Rapids, where they had a magnificent new museum. We went to Cincinnati… We went to the science museum in Des Moines. We had about 45 people from all walks to life, the Journal Star, community leaders, representatives from the Historical Society, Lakeview… [Dave] Ransburg was the mayor and he came along. And a concept began to emerge.

We developed the concept of a collaborative museum of art, history, science, technology and nature… Then we said, from what we saw on these trips, it has to go downtown, and we [suggested] the Sears Block. That was a two-year fight. Brad worked really hard on the referendum, which passed by a couple hundred votes. We brought in a museum architect, who did a study of five locations. He reinforced [our decision] and said this should be the location, and that’s how it came to be.

It’s amazing it was even pulled off…

You know, there’s a proverb [Proverbs 29:18] that says, “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” It’s so important in the community to have a vision. And we had a vision for this multi-purpose museum. I think we had a great concept, and a great location. iBi