With lofty themes and pervasive humor, the master painter delivers work of amusement and consequence.

When you talk with Ken Hoffman, he moves closer to you than you would expect. The artist’s eyes, bright and hopeful, consider yours.

He studies you, his hands in his pockets… or holding a paintbrush or dayglow marker. I’ve never asked why he does this. I think he is absorbing you: taking you in, considering you as the next bird or cat or dog whose look or character or behavior might inspire a painting. And you just might become material for one of his collaged stories.

Ideas Everywhere

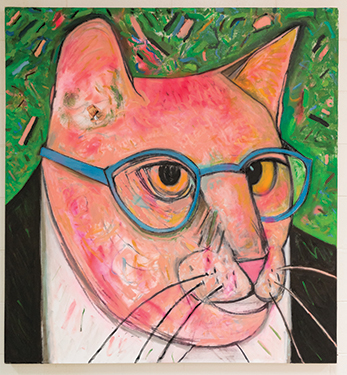

Ken is charming, genial, self-effacing. For the past 35 years, he has painted animal portraits—birds, pigs, cats, dogs, monkeys—dressing them in ties, shirts and jackets, and shaping their humanlike facial expressions to reveal how close people are to animals, and animals to people. These anthropomorphic characters allow him “to get out what he wants to say,” as he puts it—to make statements that analyze, describe and respond to a variety of events and individuals.

Ideas come from everywhere, he tells me. He and his wife Barbara, a fine art photographer, have books spread throughout their home, opened to pages of particular works of art, certain painters, or commentary such as Fred Dewilde’s Mon Bataclan—a personal reflection on the terrorist attack at the rock concert in Paris in 2015.

The Hoffmans travel frequently to take in exhibitions of contemporary and experimental art. It replenishes their spirits… suggesting what the exhibiting artist was thinking about, offering new ways to structure a painting, different materials to use.

Ken’s interest in animals draws him to wildlife magazines, where he finds figures that intrigue him: their appearance, their movement, their sense of themselves. An ostrich, for example, displays elegance and reminds Ken of an aristocrat; Ostrich Man became a popular character in his oeuvre.

He stores pictures for a long time—years in the case of the raven he recently selected as a vehicle for expressing his thoughts about the current political situation. “You never stop looking at what is before you that feeds your work,” he explains.

Ken is a master painter. The way he handles paint—layering it, dabbing it, adding brisk lines, smoothing it with his fingers—he produces work with gorgeous surfaces. “Technically,” he says, “I try to achieve painterly effects and a sensuous buildup of the paint.”

He uses color and texture to add layers of complexity to his mark making, adhering small pieces of paper and fabric to most of his paintings. “I attach anything and everything to paintings,” Ken says. “When Barb and I walk, I look at things in the street and gutter—McDonald’s hamburger wrappers, newspapers, chocolate milk cartons, old photographs—and I take them home and store them for use in my collages. I have a box of papers and things for later use.”

Creative Wayfinding

Art was new to Ken when he arrived in Japan during his tour of duty in the U.S. Navy. The schools he had attended in Texas did not teach art, and his major in college was dentistry. In Tokyo one night, he attended a museum opening of paintings from the Louvre.

“It grabbed hold of me,” he remembers, his eyes widening as if he still doesn’t believe it. “I don’t know what it was.” He saw the exhibit several times. Today, it reminds him of what sculptor Louise Bourgeois once said: “Artists are born, not made, and there’s nothing you can do for them.” With a smile, Ken adds, “Just leave them alone.”

He returned to the United States at 24 years old and graduated from the San Francisco Art Institute. “That’s really late to begin painting,” he notes. “I worked around the clock to try to catch up—to improve my drawing and painting and to learn techniques.”

The figurative imagery of his early work was laced with the social critiques that have engaged him throughout his career. By 1969, when Ken arrived in Peoria to join Bradley University’s art faculty, he longed to make murals. He found a studio—a large, open space in the old Merkle Building—that could accommodate 40-foot-long murals and 14-foot canvases, and offered sunlight through its large windows.

“At that time, I was including small animals in the corners and edges of the large murals. But the big paintings, the murals, got very tiring to do. So, I thought, what if I do smaller pieces using some of the images from the murals?” The first was a portrait of a pig. Ken gave him a suit and tie, humanizing him. “That was it!”

He soon began creating other animals on small canvases. Dressed in human clothes, they became central to his social commentary. With the smaller animals, he had found his way.

Protests in Whimsy

Today, in his studio on Sheridan Road, Ken and I exchange looks over The Raven, an 11’-x-7’ piece along the back wall. It is his Guernica [Picasso’s 1937 mural-sized, anti-war oil painting] With collaged photographs that conjure the 2016 presidential campaign, the painting records a phenomenon, he explains.

Club music beats in the background. Ken walks over to his new piranha painting, its 7’x7’ canvas to the left of The Raven. He adds a line, stands back to evaluate the new mark, and tells me stories of the people represented in his paintings over the years. At one gallery opening, he recalls, a visitor who hoped he was one of the cats or birds hanging on the wall whispered: “Am I in here?” “I had to tell him that he wasn’t,” Ken says. “‘Oh that’s too bad,’ the man said.”

Club music beats in the background. Ken walks over to his new piranha painting, its 7’x7’ canvas to the left of The Raven. He adds a line, stands back to evaluate the new mark, and tells me stories of the people represented in his paintings over the years. At one gallery opening, he recalls, a visitor who hoped he was one of the cats or birds hanging on the wall whispered: “Am I in here?” “I had to tell him that he wasn’t,” Ken says. “‘Oh that’s too bad,’ the man said.”

It was his friend, the artist Marlene Miller, who suggested the piranha photograph he had been holding onto looked like a volcano with lava flowing from its mouth. Depicting a wedge-shaped form intrigued Ken: the brightly colored head pointed upward, mouth open, teeth frightening, toenails and human fingers floating in the sky overhead. He dressed the fish in a green shirt and bow tie, humanizing it.

“What are you saying here?” I ask. “What does the piranha say to you?”

“The painting is about violence and hate,” he responds without hesitation. It is a visual protest.

Amidst lofty themes, there is often an underlying humor to Ken’s work. Talk to him about any piece he’s made and he begins to smile. Satire, irony, whimsy… his humor and good spirits shine through. His paintings are beautiful and full of meaning—ask him about them.

Ken, now retired from teaching, is able to spend his time making pictures and experimenting with materials and ideas. After all, he says, “I can do anything I want… try anything I want.”

And with all of his characteristic energy and dynamism, he reminds himself: “Go for it!” a&s