Its significance can be summed up in three words: geology, botany and people—and each is a treasure.

I don’t recall how we first heard about Rocky Glen, but it was the summer of ’93 when my friends and I first caught a glimpse. I was 16, and we were on the hunt for mystery and adventure, something out of our comfort zones, something remote and untouched by human development. When we finally located this hidden treasure, it was everything we’d imagined.

Twenty years later, on a bright, sunny May morning, I found myself heading for the same place, a bit grayer around the temples. Soon I was stumbling through a muddy creek bed, recounting my high school exploits to our tour guide and Friends of Rocky Glen president, David Pittman. Half a mile up the creek, there it was… just as I remembered. “Amazing!” I gushed.

“Welcome back,” said Pittman. “Welcome to Peoria’s newest park!”

Our Secret Neighbor

It’s been likened to a mini-Starved Rock, but unlike that popular hiking destination, Rocky Glen remains virtually unknown, even to many of its closest neighbors. But hidden away in the dense woods near Kickapoo Creek and Farmington Road lies a glorious natural area unlike any other in the region. Surrounded by moss- and lichen-covered sandstone, the world falls away, only the chirping of birds, the crunch of leaves underfoot, and the drip-drip-drip of a small waterfall to disturb the quiet.

“The glen itself was, once you got inside it, a wide chasm with high rock walls which went straight up the hillside for a hundred feet. A tiny stream of water fell over the cliff, tumbled down the rocks, and lost itself somewhere in a hidden underground current. Everything in the glen was covered with a clinging green moss. Delicate ferns grew off the rocks, and here and there a fragile flower managed to unfold a blossom without the aid of the sun, which never penetrated the glen.”

Though Rocky Glen is dynamic and ever-evolving, this poetic description, from the 1935 book Horse Shoe Bottoms by Tom Tippett—a coal miner, union organizer and journalist who grew up nearby—still holds true, some eight decades later.

Though Rocky Glen is dynamic and ever-evolving, this poetic description, from the 1935 book Horse Shoe Bottoms by Tom Tippett—a coal miner, union organizer and journalist who grew up nearby—still holds true, some eight decades later.

Opening the Glen

It’s only a few weeks after the massive flood of April 2013, when the Illinois River crested at 30 feet, breaking a 70-year-old record. Near Rocky Glen, floodwaters submerged the bridge across Kickapoo Creek at Farmington Road, closing off the intersection. Several hundred yards away, the Peoria Speedway lay underwater. “I’ve never seen it that high,” was the common refrain.

Today is David Pittman’s first hike into the glen in two months, and he’s astounded. “I’m still trying to wrap my head around it. The trail looked nothing like this,” he says, pointing at brush and debris that had washed down the hillside. “This was a very small gulley, and it’s now a huge open area. There was an over-shelter of trees that are now gone. Clearly, the channel opened up in the glen—there must have been a lot of water here.”

As we collect plastic bottles and trash, Pittman recounts how this journey began for him. “I stumbled upon Rocky Glen about a decade ago,” he explains. “In the 1970s, the State of Illinois created the Illinois Natural Areas Inventory, and biologists mapped out these areas… When I looked up the list of areas in Peoria County, I saw [Rocky Glen], and it had kind of a map.”

Already immersed in environmental causes, it was love at first sight for the West Peoria resident and former Peoria Park District trustee. Several years ago, Pittman formed the Friends of Rocky Glen to bring attention to this neglected gem, recruiting like-minded supporters to serve on its board. “I had known the landowner… and gotten permission to walk on his property,” he says. “And he gave [us] permission to start leading hikes.”

That was in late 2010. Meanwhile, the owner was looking to sell the land. The Friends group approached the Peoria Park District, who in turn led them to the City of Peoria, which had access to grant money from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources that could only be used to buy natural area land. Last December, the Peoria City Council voted 9-2 to purchase the 70 acres surrounding Rocky Glen, and with that move, this treasure of nature and history is finally poised to open up to the public.

Sands of Time

The sandstone at Rocky Glen dates back some 300 million years, to a time when Illinois was a swampy, tropical environment. “The best evidence [suggests] that Peoria was located about five degrees south of the equator,” explains Ed Stermer, earth science professor at Illinois Central College and a Friends board member. “It sat on the shore of a shallow ocean to the west and a shoreline environment to the east, where rivers draining from the Appalachian Mountains would dump their sediment. Rocky Glen represents one of those river channels.”

The coal that underlies this sandstone was forged from the “still water parts of the swampy areas, where there was a lot of plant material,” he adds. “And the shale would have been the mud in between the plant areas and the sandstone.”

The glen’s most distinctive feature, its 70-foot box canyon with seasonal waterfalls, was formed later, by glacial floodwaters far more expansive than the waters that recently submerged the area. “It probably had its beginnings after the last Ice Age… about 20,000 years ago,” Stermer notes. “This area was inundated with water from all that melting ice, and that torrent rushed down the Kickapoo Creek River Valley, carving out the canyon of Rocky Glen.”

Among the unique geologic elements in the exposed bedrock is cross-bedding, which refers to inclined layers in the rock, suggesting former sand dunes now preserved in stone. “If you look at the layering inside a lot of the rocks there…. you can see the angle where the wind would blow [the sand] up and down,” says Stermer. “It’s very prominent in the sandstone beneath those waterfalls.”

Another Green World

As we hike into the glen, Pittman points out plants along the way, from wild yellow violets to viburnums to wild hydrangea, offering a treasure trove of facts like any tour guide worth his salt. “See these mayapples, with the flower underneath? It’s a sign of healthy wildlife, as far as plants go. Over here is a jack-in-the-pulpit—this is cool. See how its flower is hidden?”

The Rocky Glen property features a rare mix of three distinct habitats: the glen itself, the prairie meadows surrounding it, and a mature oak-and-hickory forest beyond the prairies. The creek that leads to the glen is “biologically healthy,” says Pittman, and offers a habitat for plants not often found in this region. “There are frogs in this creek, and I’ve seen box turtles out here. And there’s a lot of stuff that’s unique: ferns and liverworts, the hydrophilic plant communities you see in moist environments.”

Near the glen itself, he points to the brilliant green grasses and young plants growing out of the bedrock. “This is a great example of the health of the area—a nice diversity of native plants, without any non-natives that I can see… That fern,” he gestures, “is an edible delicacy called a fiddlehead. As it comes up, it unfurls… and that’s the ‘head’ of the fiddlehead. In New England, it’s eaten all the time.

“Over here are little grass communities called hill prairies,” he continues, “with flowers and grasses that don’t grow very many places anywhere in the world. Hill prairies are one of the most endangered plant communities, and Rocky Glen’s hill prairies need a lot of work—they’re overgrown with non-native plants. Part of what I’d like to do is restore these hill prairies.”

Indeed, despite the area’s overall health, it’s an ongoing battle to control the spread of non-native species—especially in the meadows along the upper slopes. As we walk, Pittman periodically stops to pull them from the ground. “This is a bad plant—garlic mustard. Nasty, invasive, difficult to control. In a few years, this will spread unless it gets stopped—or it already has, and we just haven’t noticed.”

In the Mines

“Imagine Indiana Jones,” says Pittman, “in a rail car.” We’re standing in front of a curious hole in the hillside along the creek—an entrance to a massive coalmine that once stood on the property. This entryway—and the nearby remains of rail tracks—are the last visible signs of the mining operations that once caused violent rows on this peaceful land.

Coal was king in central Illinois, at least from the mid-19th century into the early part of the 20th, and mining history runs deep here. According to a directory published by the Illinois Geologic Survey in 2000, there are more than 650 former mines in Peoria County alone, but once you start digging, the details become pretty murky. “There’s no real good records,” Stermer explains. “These mining operations came, saw, conquered and left. But we do have a sense of the extent of the mines from old maps, surveying and other techniques.”

Coal was king in central Illinois, at least from the mid-19th century into the early part of the 20th, and mining history runs deep here. According to a directory published by the Illinois Geologic Survey in 2000, there are more than 650 former mines in Peoria County alone, but once you start digging, the details become pretty murky. “There’s no real good records,” Stermer explains. “These mining operations came, saw, conquered and left. But we do have a sense of the extent of the mines from old maps, surveying and other techniques.”

This was known as the Crescent City Mine, he says, operated by the Crescent Coal Company from 1908 to 1922. “It sloped down about 50 feet to hit the coal seam. Based on the maps, it probably went back a mile or two, and a half mile on either side.” Additional research by Mike Miller of the Peoria Park District suggests this entrance led to a maze of tunnels and chambers stretching up to 50 miles! And such underground labyrinths weren’t uncommon: according to an article by Marilyn Leyland published in iBi last year, “It was said that a miner could travel via tunnel from Hanna City all the way to Glasford.”

A coal industry publication dated February 10, 1921, suggests the property was purchased by the Clark Coal & Coke Co., after which, at some point, it fell into the hands of George Vicary, who was most likely involved with the Vicary Coal Company. In 1954, he sold it to Harold Connaughton, and it remained in the Connaughton family until last year, when Harold’s son, Jim, sold it to the City of Peoria.

Writing on the Wall

Writing on the Wall

The tension between the miners and the companies who employed them is a fascinating story, and one of great significance. (Check out Tippett’s Horse Shoe Bottoms for an extensive account of Illinois’ coal culture in the 19th century.) The story of Rocky Glen is as much about the lives of these miners—the poverty and backbreaking work conditions, the union organizing, the mining disasters which took the lives of thousands—as its plant life and geology.

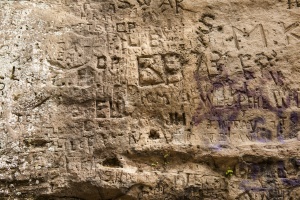

These stories are carved into the walls of Rocky Glen, where local miners once met to organize a union and labor strike. Scattered amongst more recent graffiti lies evidence of this history in a mosaic of faded carvings, some dating back to the 1880s. Most prominent among them is a hand that rises out of a crack in the stone, some sort of card in its grip, with what appear to be the letters “A-M-A” carved into it. “The card, I think, was a union card for coal miners,” says Pittman. “‘A.M.A. would have been the American Mining Association, active in the 1860s… This would have been years later, a reverent sort of carving… an emotional symbol.”

Other carvings, or petroglyphs, depict a myriad of semi-legible names and symbols. One resembles a papyrus roll; another appears to be some sort of shield, not unlike the Harley Davidson logo. Both are too weathered to know for certain. “The deep carvings are faded now,” says Pittman, “but you can see the different styles of writing… Several of the letters make me think they came from a similar timeframe. Late 19th century would be my guess.”

Lovers’ Hideaway & Cowboy Jungle

Though little-known today, in the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s, Rocky Glen was a familiar destination for many Peorians. According to Horse Shoe Bottoms, it “had at first been found by young lovers who strolled into its shadowy recesses to be alone.” Among these lovebirds were Bill and Hazel (Sommer) Rutherford, founders of Wildlife Prairie Park and Forest Park Nature Center, and partners in marriage for 62 years. According to Pittman, Bill Rutherford once told him that he and Hazel picnicked at Rocky Glen on their first date, an anecdote that could hardly be more fitting, considering the couple’s legacy in natural land preservation.

In the 1940s and ‘50s, some of the locals had another name for Rocky Glen: Cowboy Jungle. “Cowboy Jungle was visited by West Peoria kids, eight, nine, 12 years old,” says Pittman. “They’d park their bikes at Madison Park… where the Park District had a spring, fill up their bottles… and meet kids from the South Side. This is where they’d hike and play all day long.” According to one account, there was a swimming pool near the waterfall, and on hot summer days, the kids would slide down the rock into it.

“I’m willing to bet that most boys who grew up in Bartonville or on the South Side through the 1950s had visited, or at least heard stories of Rocky Glen,” says Marilyn Leyland, for whom the location is a family affair. “Manual High School biology students went there on field trips in the 1930s, and probably told subsequent generations about it, or, like my dad, took their kids there. My Girl Scout troop went there for a hike in the ‘50s when a classmate’s grandfather owned the property. The noted botanist Irene Cull was with us, explaining plants along the way. Meanwhile, my classmate kept urging friends to hurry up because she couldn’t wait to show everyone the big rock!”

Leyland’s grandfather, John Voss, taught science and was later principal at Manual. He was active in the Peoria Academy of Science, which campaigned to preserve Rocky Glen as a public park as far back as the 1930s. Her sister, Carolyn “Cookie” Radosevich, remembers the petroglyphs—“I’d never seen so many names and initials carved everywhere”—while her husband, John Leyland, also recalls a scouting expedition to Rocky Glen—“an exhausting summer hike in the early 1960s”—which began and ended at St. Bernard’s School, a good ten-mile slog, round-trip.

When it comes to uncovering the history of Rocky Glen, these stories are just the tip of the iceberg; what’s difficult is sorting fact from fiction. Was the Shelton Gang, that infamous band of brothers who controlled gambling and vice in Peoria in the mid-20th century, familiar with this place, as has been alleged? And if so, might it have been used in their criminal exploits? Given the time period—and the location of Bernie Shelton’s farm nearby—it’s certainly possible. But as with the mining history and those names carved into bedrock, it’s yet another puzzle, however fascinating, that’s likely to remain unsolved.

Welcoming a New Generation

For the last half-century, just a handful of people have been able to experience Rocky Glen up close, but that is changing. Having brought the park back into the public eye, and with the support of the City of Peoria and the Peoria Park District, the Friends of Rocky Glen are working hard to see to that. “We would like to put in a parking lot so it can be open dawn to dusk,” says Pittman. In the meantime, the group is raising funds and leading monthly hikes on the property, in addition to clearing non-native species from the prairie meadows and cataloging the area’s unique biological and geological elements. If all goes well, Rocky Glen is set to become a regional attraction in the not-so-distant future.

“I think more people need to get out there,” says Stermer, who envisions Rocky Glen as a designated geoheritage site, actively managed to conserve its unique features for future generations. “It’s a record of the geology 300 million years ago, it’s a record of the coal miners and their strife 100 years ago, and it ties all that together. I think the coal mining history of Peoria is lost to the latest generation. If we can preserve that mineshaft, and if we can preserve those carvings and sketchings… that would serve as a reminder to the cultural history of the area, and it’s also a beautiful testament to the natural and geologic landscape of the area.” a&s

Monthly hikes at Rocky Glen continue throughout the rest of 2013! Upcoming dates include July 20th, August 3rd, September 14th, October 12th, November 9th and December 7th. Meet in the parking lot at Jimmy’s Bar, 2801 W. Farmington Road in West Peoria, a little before 10am, and plan for a two-hour hike. Visit friendsofrockyglen.org for more information.