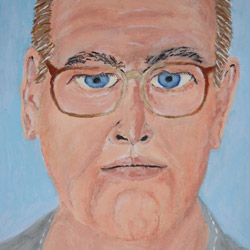

“You can express yourself in art when you can’t always find the words to express yourself.”

—Steve Love, brain injury survivor

Steve Love’s life was forever changed on September 11, 2004, when three deer darted across the highway and caused him to lose control of his car. Two weeks later, he awoke in a hospital bed with no memory of the accident, his rescue or the helicopter flight to the emergency room. Love had sustained a traumatic brain injury. The left side of his brain—the part in charge of words, cognitive thinking, and math and science skills—was severely damaged, which presented daily challenges. “It’s [now] so hard to do even the simplest things,” he said.

A painter since youth, Love had stepped away from his hobby for several years but found a renewed interest in putting brush to canvas shortly before the accident. Later, as part of the healing process after sustaining a traumatic brain injury, he attended a conference sponsored by the Brain Injury Association of Illinois and was greatly inspired by a workshop on art therapy. Using his hobby to aid in the healing process sounded like a great idea to Love, who went home intending to give it a try.

“I don’t always have control over how I react, but when you sit down with a blank canvas,” explained Love, “you are in control; you make that canvas come alive how you think it should come alive.” Gaining this control, while it may seem like a small victory, has boosted his confidence and greatly enhanced his quality of life.

“Painting is now one of my joys in life,” he affirmed. “I see the world using mainly the right side of my brain. I see patterns where before I saw nothing. The more I exercise the right side of my brain, the better artist I become.”

Love’s self-directed therapy has helped him make great strides in his physical and cognitive recovery. An artist who paints from photographs, Love said that the double vision caused by his accident makes it difficult to focus on an image and paint what he sees on the canvas. At first, he could only work for short periods, but his ability to focus gradually improved, allowing him to spend more time at the easel. Now, he’s able to paint for up to two or three hours each day. In addition, performing the delicate movements that painting requires has helped Love improve his motor skills and regain control over his body.

A Healing Profession

A Healing Profession

While Love’s therapy is self-taught and directed, art therapy itself comprises an entire professional field within the sphere of human services. The American Art Therapy Association (AATA), an organization that promotes the field and provides standards for its practice, says that by creating art and reflecting on its processes, people who experience illness, trauma and other challenges can “increase awareness of self and others; cope with symptoms, stress, and traumatic experiences; enhance cognitive abilities; and enjoy the life-affirming pleasures of making art.”

While records of art in clinical situations date back at least a century, the creative process has been used for its therapeutic qualities since the beginning of time. Anyone who has created a piece of art, no matter how amateur, has realized firsthand its remedial nature. “This seemingly irrepressible urge to make art out of any available materials confirms the compelling power of artistic expression to reveal inner experience,” says the AATA. “It was because art making provided a means of expression for those who were often uncommunicative that art therapy came to be developed as one of the healing professions.”

The educator and psychotherapist Margaret Naumburg is credited with establishing the field of art therapy in the U.S. She founded the Walden School in New York City and wrote several books on the subject and its practical applications in the 1940s and ‘50s. About the same time, artists who volunteered in mental hospitals during the war were attempting to convince psychiatrists of the benefits art therapy could provide to their patients.

Founded in 1969, the AATA was the first national professional organization for art therapists. The 1970s saw the first graduate degrees awarded in the field, paving the way for today’s educational opportunities. In addition to the 33 AATA-approved master’s programs, including one at Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville, bachelor programs such as that at Decatur’s Millikin University have arisen to train prospective therapists in the healing qualities of the arts.

Today’s licensed art therapists are trained in both art and therapy and are recognized by the Art Therapy Credentials Board. Their careers are comprised almost exclusively of using art therapy to help people work through the challenges in their lives. Other professional counselors, like Dr. Lori Russell-Chapin of Chapin & Russell Associates in Peoria, utilize art therapy alongside traditional counseling methods.

Russell-Chapin uses such “alternative methods counseling” with about one-third of her clients. Besides the visual arts, Russell-Chapin utilizes many other artistic mediums in her therapy methods, such as dance, drama, music and literature.

Emphasizing the Strong Suit

Emphasizing the Strong Suit

“If you ask your client who they are and they say, ‘I’m a wonderful musician,’ you’ve got to go with that strength,” explains Russell-Chapin. “It’s a way to build rapport, and it’s something they’re good at. Wouldn’t you want to use something that someone’s good at to help them get at something that perhaps they feel insecure about?”

She notes that this technique isn’t just for clients whose strength lies in the traditional creative arts, but works for those with interests like gardening and carpentry as well. Take the gardener, for example. When asked what is required to create a beautiful garden, the client might respond that it takes nourishing, weeding and watering. Russell-Chapin can use that analogy to show that the same principles apply to overcoming hurdles in life—that it takes work.

“You’re constantly trying to build new resources with people through imagery,” she explains. “Sometimes it’s hard to say, ‘I’m really struggling, and this is what’s wrong with me,’ but it’s not so hard to do it in story, in art, in symbol, or in dream analysis.”

Russell-Chapin found that one of her clients enjoyed writing stories. Using that strength, he was able to tell about his struggles coping in life without having to come right out and say it. His story made it much easier for the counselor to understand where he was coming from and help him see how to work through it.

Dr. Russell-Chapin also employs mask-making in art therapy sessions. On the outside of the mask, her clients draw the parts of themselves that they allow the outside world to see, and on the inside, those things they hide from the world. Just like writing a story, the artistic act of creating a mask can be an easier method of communicating such topics than struggling to find the right words to describe them. When the masks are completed, Russell-Chapin works with clients to determine why these things are shown to or hidden from others.

“I think the benefit is that [art therapy] allows the client to step away from their situation, so it almost serves as a buffer,” says Russell-Chapin. Because clients often don’t know what she’s looking for in art “assignments,” she can get to the specifics much more quickly than with traditional cognitive approaches. In the latter approach, clients tend to filter their responses through internal questions: “What is she going to think about me?” or “Can I really tell her?” Art therapy produces more honest—and less self-conscious—results.

Not only do activities like painting, mask-making and writing help people express feelings for which they cannot find words, they also offer the therapeutic qualities of creation. In fact, the entire profession was originally divided into two schools of thought. Some therapists believed that the act of creating art alone produced most of the therapeutic qualities, while others thought the benefits came more from talking about what was created. Today, as is often the case, a combined approach is believed to provide the best results—the healing benefits derive both from the creation of art and the subsequent discussion about it.

Art therapy continues to evolve as a professional discipline as more students enter specialized programs and human service professionals realize its benefits. Those who have tried it certainly have positive things to say. “One of the greatest joys I have now is when I sit down at the art studio table in my house—it’s when I feel most in control,” says Steve Love. And that feeling, for anyone who has lost control of parts of his or her life, is priceless. a&s