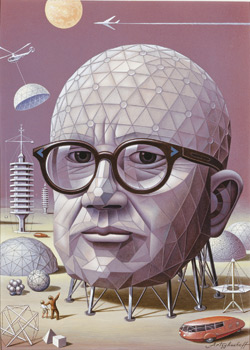

Architect, philosopher, author, educator, mathematician, designer, futurist and inventor, Richard Buckminster “Bucky” Fuller (1895-1983) was one of the most visionary thinkers of the 20th century. While best known as the inventor of the geodesic dome, his theories and inventions encompassed fields ranging from mathematics, engineering and environmental science to literature, architecture and visual art.

Communications theorist Marshall McLuhan called Fuller “the Leonardo da Vinci of our time.” He believed in the interconnectedness of all things and devoted his life to closing the gap between the sciences and humanities that he felt prevented a comprehensive view of the world. His work foresaw advances in technology, the rise of globalization and the green movement decades ahead of their time, and continues to influence today’s artists, designers, engineers, environmentalists and mathematicians.

I was first introduced to Bucky, as he is affectionately known, in the mid-1990s, when I stumbled across the curiously-titled Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth at a local bookstore. Intrigued, I took it home and read it cover to cover. It is no exaggeration to say that I had never experienced a mind quite like Buckminster Fuller’s.

I’ve always been attracted to those who crossed disciplinary boundaries, whose life could not be summed up by a job title or defined by a single accomplishment. The more I learned about Fuller, the greater inspiration I drew from him. He framed the world’s problems in bold, innovative ways, with a practical emphasis on “what works.” This approach made a lot of sense to me.

In the 1960s, at the height of the counterculture, Fuller was a popular figure on college campuses. Somehow, this 70-something professor became hip to a generation that claimed not to trust anyone over the age of 30. With an intellectual curiosity that often recedes as one grows older, he offered a different approach to progress, one that resonated with a generation that questioned authority in all of its forms.

When I learned that an exhibit of his work was coming to Chicago, it had been nearly a decade since I last immersed myself in Bucky’s world. It didn’t take long to recall just why he fascinated me in the first place.

Starting With the Universe

Through June 21st, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Chicago will host Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe, the first major U.S. exhibition of Fuller’s body of work in more than three decades. On the heels of a 2008 run at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, the MCA is the only other institution in the country to host the exhibit.

On March 13th, I was privileged to attend a preview tour of the exhibit with MCA Chief Curator Elizabeth Smith. Also attending were Allegra Fuller Snyder, Bucky’s only living child, and his grandson Jamie Snyder, co-founders of the Buckminster Fuller Institute, which they established in 1983 to continue Fuller’s legacy in art, science, design and technology. Their commentary provided a unique perspective on this “intensely passionate, prolific and idiosyncratic individual.”

The exhibition assembles hand-drawn sketches, letters, notebooks and other artifacts from collections both public and private, alongside wall-sized photographs and maps, movie clips, and scale models of many of Fuller’s projects, including his famous geodesic dome. Many are on display for the first time.

It is a walk through the 20th century via the mind of one of its most original thinkers. Einstein’s theory of relativity, the birth of the automobile and airplane, the Great Depression, both World Wars, Vietnam, post-modernism, the counterculture, the energy crisis, the computer revolution—these form the contextual framework with which Fuller’s work is intertwined. For while his ideas were light years ahead of his time, he was also very much of his time.

The show is jam-packed with information representing six decades of an integrated approach to housing, transportation, communication and cartography. Amidst today’s seemingly intractable problems, Fuller’s worldview resonates more strongly than ever. He offers a clear path forward: a positive, practical approach to problem-solving; holistic thinking about interconnected systems; and the tremendous potential of human beings as drivers of change.

Strolling through the galleries, it’s difficult to fathom how this man accomplished so much in a single lifetime. The breadth of the collection illustrates one of Fuller’s principal concepts, that of synergy, the word he coined—that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. While any one of his inventions, designs or theories is incredible on its own, when stitched together as a mosaic of sorts—the sum of the life’s work of one man—it truly becomes a thing of beauty.

Who is Buckminster Fuller?

“There are many Buckminster Fullers,” says Harvard professor Antoine Picon in the book which accompanies the exhibit. Truer words were never spoken.

Richard Buckminster Fuller was born in 1895 in Massachusetts. His great aunt, Margaret Fuller, was a transcendentalist writer who co-founded a magazine with Ralph Waldo Emerson. As a boy, he showed a natural curiosity and propensity for design and construction. He spent time at Harvard, worked at various industrial jobs, served in the U.S. Navy during World War I, and married Anne Hewlett in 1917.

In 1922, Fuller lost his daughter to complications from polio and spinal meningitis, which devastated him and drove him to drink. Several years later, bankrupt and unemployed, he stood on the shore of Lake Michigan in Chicago and considered taking his own life. But through the darkness, Fuller experienced a spiritual rebirth which would alter the course of his life. At that moment, he dedicated himself to discovering what a single individual could do to change the world for the benefit of all humanity.

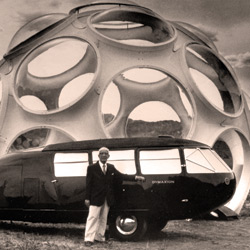

Within several years, he had coined the term Dymaxion—from the words “dynamic,” “maximum” and “ion”—which represented the efficient use of resources and self-sustaining technologies. Under this banner, he would unfold a series of remarkable inventions over the next half-century, ranging from lightweight, portable homes and aerodynamic cars to his famous geodesic dome.

Fuller managed numerous companies, directed research and consulted with architects around the world, from Great Britain to Israel to India. He worked with the U.S. Army and Fortune magazine, the Ford Motor Company, aircraft and manufacturing companies, and railroad car manufacturers. He served as the second president of Mensa, authored more than 25 books, and was awarded 28 U.S. patents and many honorary doctorates. He even had a molecular structure named after him! Discovered in 1985, the buckminsterfullerene, or buckyball, consists of 60 carbon atoms arranged much like Fuller’s geodesic dome. The 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for its discovery.

From the mid-1950s to the early ‘70s, he was a professor at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, which served as his home base for many years. He also taught at Cornell, Washington University, Chicago’s Institute of Design and Black Mountain College—where he collaborated with artists like John Cage, Willem de Kooning and Kenneth Snelson—and lectured at hundreds of others. In 1962, he was named professor of poetry at Harvard.

In the mid-‘60s, Fuller was chief architect of the U.S. Pavilion, a geodesic dome built for Montreal’s Expo ’67, the most successful World’s Fair of all time. He proposed a series of urban renewal projects, from the renovation of Harlem and the floating neighborhoods he designed for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to the domed city he envisioned to solve the housing crisis in East St. Louis. For a variety of reasons, many of these projects never came to fruition.

It is impossible to fully describe Fuller in a handful of pages. Throughout his life, he compiled his correspondence, notes and sketches into what he called the Dymaxion Chronofile. This project, now housed at Stanford University, consists of 150,000+ letters, 10,000 slides, 600 hours of audio tape, millions of inches of news clippings, and on and on. When it was eventually bound, it numbered an astonishing 847 volumes! Archivists have called Fuller’s life “the best documented” in history.

A Life’s Work, Ongoing

For all of his efforts, Fuller’s visionary ideas were never fully realized in his own time. But more than 25 years after his passing, it is becoming clearer that he was on to something big. His early advocacy for renewable energy, especially, seems downright prophetic, and he is considered by many to be the “godfather” of today’s sustainability movement.

The MCA exhibit brings Fuller’s work full circle into the 21st century, proclaiming his ideas “ripe for reexamination by artists, architects, designers, scientists and poets, among others.” Indeed, they seem to be more relevant than ever. As his daughter, Allegra Fuller Snyder, proclaimed at the preview in March, “Much of Bucky’s work remains unfinished.” a&s