The Modern Glass Movement

The art of glass blowing can be traced back to first-century B.C. Syria, then a province of the Roman Empire. Spreading throughout the Roman world, the art form made its way back to Italy, where Italians became masters of the craft. In the late medieval period, the city of Venice—in particular, the island of Murano—became a hotbed of the glassmaking industry where many of the techniques of glass blowing were developed.

In 1962, the “studio glass movement” was born, defining glass as a fine art medium. The catalyst for this movement was a series of workshops held that year at the Toledo Museum of Art. At these workshops, ceramicist Harvey Littleton and scientist Dominick Lambino shared the results of their experimental studies with glass, establishing the traditions of the movement. These two revolutionary men proved that an individual artist could work with this medium in a studio setting.

Local glass artist Hiram Toraason of Toraason Glass describes this crucial development as “taking glass out of a factory setting and putting it into an artist’s hands to create fine art.” Following these workshops, Littleton, the founder of the modern American studio glass movement, began teaching the first glass blowing class at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Local glass artist Hiram Toraason of Toraason Glass describes this crucial development as “taking glass out of a factory setting and putting it into an artist’s hands to create fine art.” Following these workshops, Littleton, the founder of the modern American studio glass movement, began teaching the first glass blowing class at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Our own city of Peoria even played a role in the early days of the movement. Those students who benefited from the first courses offered by Littleton took the experience and spread their knowledge across the United States. One of these students, Bill Boyson, was part of this first generation of the modern glass movement. In 1965, Lakeview Museum sponsored Boyson, then at Southern Illinois University (SIU) in Carbondale, to build a glass furnace on the back steps of the museum to form glass creations for children. This was the birth of the fine art glass movement here in Peoria.

“Glass had always been very private and secretive,” explains Toraason. “Boyson’s trip really helped to change that, opening [the movement] up to the public eye.”

Toraason later studied under Boyson at SIU and has since acquired four original Boyson pieces, made when he worked at Lakeview, which Toraason houses at his studio. Through these pieces, he enjoys sharing Peoria’s glass history with anyone who walks through his studio doors. Boyson’s students now travel the country, educating the masses on the history of studio glass art in the United States with his mobile glass unit.

From Business to Blown Glass

From Business to Blown Glass

Hiram Toraason grew up in Peru, a small community in northern Illinois. In high school, he experimented with oil painting, ceramics, printmaking and bronze casting. Despite his rich background in the arts, in the spring of 1997 he enrolled in the business program at SIU, taking art classes as electives. At that point in his college studies, changing majors was not an option, but in the end, the arts won out.

After studying in Costa Rica for several months and rethinking the direction in which his life was headed, Toraason returned to college, making the decision to concentrate more heavily on the arts. There he studied under Boyson until his retirement, spending the remainder of his studies under the direction of Che Rhodes. Rhodes’ approach to glass was more methodical than Boyson’s unconventional, free-spirited artwork, and Toraason credits the mixture of these two styles for his growth as a glass artist.

After college, Toraason moved to North Carolina to live with other artists and work as an apprentice under William and Catherine Bernstein outside Asheville. Working for the Bernsteins each morning and for a production glass company in the evenings, Toraason was eventually able to put enough money away to build the studio he has today.

“The Midwest is where I feel I need to be.”

After nearly four years of working as a full-time artist in North Carolina, Toraason decided to move back to the Midwest. “Once you leave, you realize why you love the area so much,” he explained. He and his wife Holly arrived in Peoria in 2003 to be near family members and start their own family, which now includes two-year-old daughter Naomi. At the time, he was unaware of the resurgence of arts in the area.

Since his return, Peoria has continued to impress Toraason for its support of local artists. Describing Peoria as “a small Chicago,” he appreciates that people here look at him as a viable artist.

After breaking ground with his studio in 2003, Toraason says, he never looked back. The Toraason Glass studio, tucked away on Morton Street off Adams near Constitution Park, has become a gathering place for students, artists, friends and family who come to observe the artistic process, view new work and just “hang out.” Toraason is happy that his studio can serve as an oasis for this community.

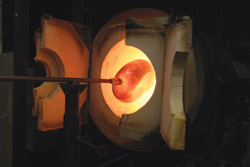

The studio itself is comprised of three furnaces. One furnace stores the clear glass, heating the molten liquid until it’s ready for shaping. The second is used to reheat the glass pieces during the process—if the temperature falls below 1000 degrees, the glass will crack. The last furnace, called the lehr, or annealer, cools the formed glass slowly, preventing cracks during the cooling process.

The studio itself is comprised of three furnaces. One furnace stores the clear glass, heating the molten liquid until it’s ready for shaping. The second is used to reheat the glass pieces during the process—if the temperature falls below 1000 degrees, the glass will crack. The last furnace, called the lehr, or annealer, cools the formed glass slowly, preventing cracks during the cooling process.

He explains that building a studio from the bottom up was “quite the mountain to climb”—and by “bottom up,” Toraason is not lying. Three months before he began to create glass art in this new building, he set about to construct the pieces necessary to form the furnaces. His furnaces are powered by gas, with one running 24 hours a day; therefore, a day off can cost him money. “The studio owns me,” he jokes. “We are the truck drivers of the arts and crafts world. Our wheels are always spinning.”

Although the hours can be long and tiresome, Toraason is a man passionate about his work, proud that he has been able to turn the hobby he loves into a career. He even goes so far as to compare his first furnace to having a new child. “It kept me up at night,” he recalls, laughing.

“I found it and it found me.”

Toraason uses this phrase to describe the way he discovered his passion for glass art. As soon as he walked into the glass studio at SIU, the heat surrounded him, and he was hooked. “Glass is a very fascinating medium,” he says, “almost like playing an instrument.”

And the way Toraason “plays” his instrument is an incredible thing to watch. Twirling the rod, or blowpipe, with the orange glow of the 2000-degree-plus melted glass on the end, he appears to be spinning a song on the violin. Watching Toraason in his element is like observing an exceptionally graceful dance—gliding from one furnace to the next, in and out of the heat, then smoothly sitting down to shape the glass with newspaper or handmade wooden tools. The crescendo of the “music” heightens as the piece begins to take shape, with Toraason flattening the glass with wooden paddles, flames shooting out in front of his face. Tension is in the air as he separates the glass from the blowpipe onto a second steel rod, called a puntil, a switch of the axis in one fluid motion. And this is just another day in the studio.

And the way Toraason “plays” his instrument is an incredible thing to watch. Twirling the rod, or blowpipe, with the orange glow of the 2000-degree-plus melted glass on the end, he appears to be spinning a song on the violin. Watching Toraason in his element is like observing an exceptionally graceful dance—gliding from one furnace to the next, in and out of the heat, then smoothly sitting down to shape the glass with newspaper or handmade wooden tools. The crescendo of the “music” heightens as the piece begins to take shape, with Toraason flattening the glass with wooden paddles, flames shooting out in front of his face. Tension is in the air as he separates the glass from the blowpipe onto a second steel rod, called a puntil, a switch of the axis in one fluid motion. And this is just another day in the studio.

Toraason’s artwork encompasses everything from functional glass tumblers to bulbous ornaments to one-of-a-kind vases. His studio walls host several large circular “plates,” which are very difficult to make because of the amount of surface area to be covered. Other colorful works lining his walls have an almost frosted look to them. The glass within these pieces is not transparent and so does not allow light to pass through. These pieces were sandblasted after their creation, helping to bring out colors that would not be as bright in the transparent realm.

Toraason’s artwork encompasses everything from functional glass tumblers to bulbous ornaments to one-of-a-kind vases. His studio walls host several large circular “plates,” which are very difficult to make because of the amount of surface area to be covered. Other colorful works lining his walls have an almost frosted look to them. The glass within these pieces is not transparent and so does not allow light to pass through. These pieces were sandblasted after their creation, helping to bring out colors that would not be as bright in the transparent realm.

Working with glass is not just a one-man show. Toraason’s assistant, Ross McIntosh, has worked with him for three years now. McIntosh’s interest in glass art came about after he saw the medium and could not figure out how it was created. “When I buy something I want to know how everything works,” he explains. It was this fixation which led to his partnership with Toraason. The two men use very few words with each other during the creation of the glass pieces; most of their communication is nonverbal or already understood.

Toraason describes the notion of working without others’ helping hands as limited—“having people around me makes it worthwhile,” he says. In fact, teams of up to twelve are not uncommon in this business. While Toraason does not have twelve assistants, he does delegate specific tasks to his helpers. This includes constant spinning of the rod so gravity does not cause the hot liquid glass to fall and heating new pieces of glass while he prepares the other piece to be joined. “Every 30 seconds we are reentering the kiln—the bigger the piece, the more hands you need to help.”

Commissions of Compassion

Commissions of Compassion

As an artist, Toraason plays an active role in the community, working with various non-profit groups and other organizations. This year, the Alzheimer’s Association enlisted him to create a Christmas ornament (see page 16) to help raise funds to fight the disease. Working closely with the organization, Toraason developed the colors and shape of the glass to clearly convey the mission behind the ornament.

“There is a certain integrity behind this piece,” he explains, “a presence behind this piece which I hope to convey. Each piece of artwork is defined by the experiences of the people it comes into contact with—that is as much a part of the art as my creating the piece.”

When asked about his most unique artistic endeavor, Toraason describes his experience working with Caterpillar. In 2006, the company approached him to design a one-of-a-kind sculpture to celebrate its engineers who had registered a certain number of patents. Toraason’s piece, the Innovator’s Award, represented a “thank you” to those outstanding engineers for all they had accomplished for the company. The Innovator’s Award was even featured in the Caterpillar parts catalog—the only “part” that cannot be purchased. He describes the Caterpillar folks as a “great group of people to work with, who believe that it is a wonderful idea for an artist to make a one-of-a-kind piece that cannot be purchased at any price.”

When asked about his most unique artistic endeavor, Toraason describes his experience working with Caterpillar. In 2006, the company approached him to design a one-of-a-kind sculpture to celebrate its engineers who had registered a certain number of patents. Toraason’s piece, the Innovator’s Award, represented a “thank you” to those outstanding engineers for all they had accomplished for the company. The Innovator’s Award was even featured in the Caterpillar parts catalog—the only “part” that cannot be purchased. He describes the Caterpillar folks as a “great group of people to work with, who believe that it is a wonderful idea for an artist to make a one-of-a-kind piece that cannot be purchased at any price.”

Clearly moved, Toraason expresses the joy which the engineers portrayed when they received the awards he had created. “By having an individual artist behind this award, the gesture meant a lot to the engineers,” he said, noting that this piece of art symbolizes the creativity behind each of their own engineering 2007work. “ It wasn’t just a monetary factor; Caterpillar went above and beyond to show these engineers their appreciation for them.”

The Art of Integrity

Toraason has a genuine respect for the role of art in society and is protective of both his own artwork and the artwork of others. “How do you copyright art?” he muses. “How do you copyright an idea?”

When asked if he would ever refuse a commission, he says he would never do a reproduction of another artist’s work, citing Dale Chihuly, another member of the first generation of the modern glass movement, as an example. “I would never make a reproduction of a Chihuly piece. There is no integrity in that.”

“I take a lot of pride in what I make and where I put it. I’d like to think that everything I create is art.” a&s